An extract from Hardman & Co's "The Monthly, November" by Keith Hiscock CEO, Hardman & Co

Referring to changes in expectations in company statements is laudable, but many investors have no idea what the expectations were in the first place.

Share prices are built on expectations - expectations about all sorts of things, such as a company’s future sales growth, the trend in margins and the profits it can return. Understanding those expectations and how they move is critical to share price formation.

Listing rules require quoted companies to update investors on progress relative to expectations. What managements often fail to understand is that many of their key investors do not have access to brokers’ research and, thus, cannot put management statements into context. It is these very investors that can cause shock movements in share prices on announcements in limited trading.

In September this year an AIM-listed company with a market capitalisation at the time of approximately £200m announced its half year results. Some elements of the statement caused concern, but institutional investors were soon reassured by the house broker’s research note and, no doubt, conversations with the analyst and his sales team. Other investors could not see that research, let alone talk to the broker. They drove the share price down sharply.

By the end of the day, it had collapsed by 20% and has now fallen 45% since that fateful announcement. What has probably shocked the management is that the price moved so much on so little turnover. In fact, on the day of the announcement only 0.2% of the shares changed hands – yes, small investors cratered the share price by turning over less than half a per cent of the register.

The life and blood of share prices is information. In a perfect market, all investors would know all the information that is relevant to their companies and the share price would reach an equilibrium between buyers and sellers. When new information is published they would assess this against their previous standpoint and buy or sell to get to a new equilibrium.

Thus, expectations are critical - expectations about all sorts of things, such as a company’s future sales growth, the trend in margins and the profits it can return. Understanding those expectations and how they move is critical to share price formation. Unfortunately, not all investors have access to the same information and many are discriminated against.

For example, although retail investors accounted for 30.6% of ownership in the AIM market in a recent Office for National Statistics survey (see our article in the October 2015 Hardman Monthly, ‘Why AIM company management ignore retail investors at their peril’) they generally have no access to institutional brokers’ research and numbers, which is reserved for the brokers’ paying institutional customers.

Companies might take pride in keeping investors informed through statements – what they may not realise is that a very large part of their shareholder base cannot properly assess this information and are, in effect, being treated like mushrooms.

In every market, listing rules include a requirement for quoted companies to make regular updates to the market and investors. This is typically, as a minimum, done through statements at the time of the publication of final and interim results (though some UK companies have tried the US convention of quarterly reporting) and occasional trading updates in between. In the UK most companies will make a brief announcement about trading at the close of the half and full year, but before the audited accounts have been prepared.

“Managements and boards are under an obligation to keep investors up to date”.

Managements and boards are under an obligation to keep investors up to date. If the business is performing better or worse than expected, or even in line, they should tell investors. If they do not, then there is a risk that a false market will be created. Heaven forbid if managers or directors should deal in their own shares, knowing that the market is under- or over-estimating a key variable – this would amount to insider dealing, a criminal offence.

How often do companies refer to expectations?

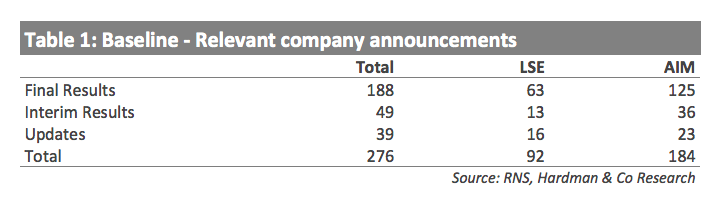

Hardman & Co has conducted an in-depth analysis of a sample of company announcements data. We have examined all the RNS announcements in June 2017. There is nothing unusual about June, except that it is a popular month to announce final results, typically for companies with March year ends. Table 1 shows the raw data for companies reporting in June 2016. It excludes any announcement that would never include reference to ‘expectations’, such as those relating to directors dealing, changes in the holding of a major shareholder etc. The weight of final results in the mix is clear.

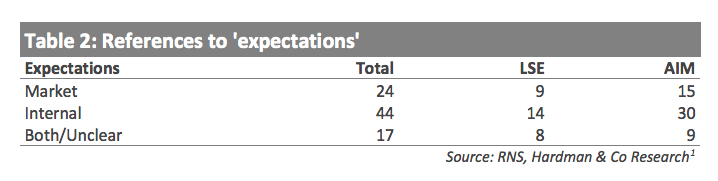

Having stablished the number of relevant announcements in June 2016 we then interrogated the database to ascertain how often ‘expectations’ are referred to. This analysis is set out in Table 2.

We have divided references to ‘expectations’ into internal or external. When we talk about external we mean market expectations – this is what brokers’ analysts (or, for many small companies, just one analyst) are forecasting for sales, profits or earnings. ‘Internal expectations’ are usually marked by reference to management or board expectations.

“Investors who are not clients of the institutional brokers that publish forecasts have no access to ‘market expectations…"

Investors who are not clients of the institutional brokers that publish forecasts have no access to ‘market expectations’ so this comment is meaningless to them. Some investors are particularly suspicious of the terms ‘Board and management expectations’ because they are not externally verifiable. However, many in the capital markets advisory community will argue that the distinction between external and internal is a fine one, because if it becomes clear to the management or board that the market’s expectations for key indicators is materially different from theirs then they are duty bound to make a statement.

The question usually arises of when can the company be sure (for example, one bad month for sales is probably insufficient evidence) and what is ‘material’. This is often the cause of investor anger when it turns out that directors dealt shortly before an announcement.

The ‘Both/Unclear’ row covers to two categories. Some companies talk of both external and internal expectations in the same statement; Flowtech announced on the 1st June that: ‘trading continues to be in line with management expectations…. we fully anticipate that Group trading for the 2016 financial year will meet market expectations’.

Others refer to ‘expectations’ without clarifying which sort; Chroma told us on 8th June: ‘The Directors consider that underlying trading is robust with turnover expected to be slightly above expectations’, whilst, on the same day, Zambeef said: ‘As a consequence of this strong operational performance, the Board is confident of meeting full year expectations’.

The data shows that two-thirds of all companies felt there was no need to refer to expectations in a statement, presumably because they were performing in line. However, on the face of it, it is difficult to explain the difference between fully listed companies (41.9% reference expectations) and AIM stocks (only 29.8% reference). Do AIM companies really perform consistently more in line with expectations thankfully listed ones? Our suspicion is that as a company’s market capitalisation grows (on average AIM stocks are smaller) its effort to communicate with shareholders increases, and it is more in the spotlight, hence more reference to expectations.

We understand that on many occasions the investor relations advisors to companies have tried to help inform investors when using the term ‘expectations’ by adding in brackets what the consensus numbers are on Reuters, for example, only for that part to be struck out by the broker to the company. No doubt the argument is that if the company refers to a specific number it would need to prove where that number came from if things go wrong, so as to avoid endorsing a number; others may suspect this is a way of locking some investors out of the loop.

Conclusion

Keeping investors informed about the progress of their companies is important in creating both a transparent and an efficient market. However, companies should recognise that many investors, and particularly retail ones, may not have access to the research of brokers which forms expectations. They should not be surprised if these ‘under-informed’ investors react differently to traditional institutional investors.

For many small and even mid-cap stocks these investors provide the daily liquidity in shares which sets the price. Ignoring their needs courts disaster, as the management of the company referred to in the opening paragraph found. Companies should consider employing a firm (such as Hardman) which can provide research and forecasts to all investors to work alongside its house broker.

.png)